There were many aspects of a woman’s costume that showed society how wealthy she was. This can be seen in the restrictiveness of her clothing but also in the construction and details of her garments and outfits. A woman dressed in confining clothing demonstrated to the public that she was an “elaborate and expensive object”1 that could afford not to do housework.

The Sewing Machine

1870 Sewing Machine

With changing technology, the aspects of the garments that demonstrated wealth changed. Sewing machines made creating garments easier, which meant that middle-class women could afford dresses that looked more expensive. With this change, upper-class women “attempted to retain uniqueness of their social level”2, through having different dresses for different times and events of the day. Before sewing machines “upper-class women, who had utilized excessive dress trimming to differentiate themselves from the middle and working classes, now chose instead to use expensive and fragile fabrics that would have been impractical for those without a great deal of disposable income.”3 Sewing machines forced upper-class women to find a different way to distant themselves from the classes below them.

Electricity

Gilded Age Parlor

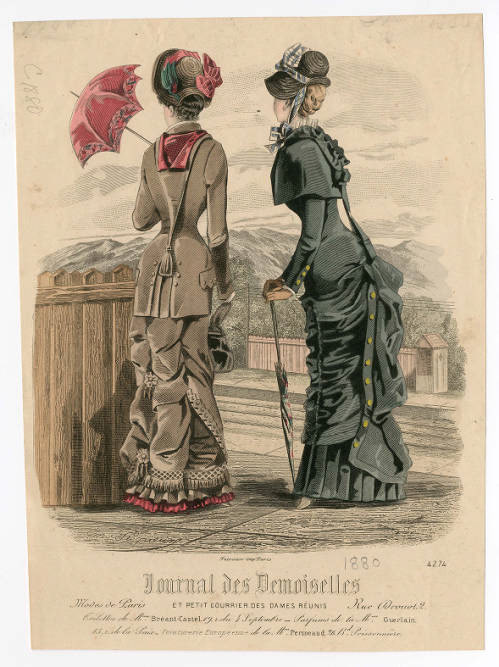

By 1870, wealthy women had different articles of clothing for “receiving guest, visiting others, traveling, attending church, and attending weddings.”4 With the invention of electric and gas lighting came more time to socialize, which also meant a woman now needed additional dresses for the additional times of day. Wealthy women were able to afford many different styles of dresses, while middle class women could not to the same extent.

A wealthy woman spent massive amounts of time getting dressed every morning and changing throughout the day and keeping up on fashion trends was not an easy task, since the silhouettes changed dramatically. Being able to keep up with these trends and owning different dresses designed for different times of day was a sign of wealth.

While it is true that sewing machines made creating garments easier, in the end they did not cut down the time it took to make the garment. Standards and expectations of garments rose along with the popularity of the sewing machine. But as it became easier to make garments, upper-class women had to find ways to make their wealth visible as it became easier for middles class women to copy the fashions. These upper-class women did this by having different dresses for different times of day along with using more expensive fabrics. In response middle class women used more extensive ornaments in their dresses, to attempt to make their outfits look like the clothing that wealthy women wore.

Wear and Tear

In addition to having a variety of dresses, wealthy women often chose fragile fabrics to show that they did not have to do manual labor nor activities that could potentially damage their dress. These fabrics could not be easily cleaned or repaired so these garments suggested the idleness that the wealthy woman could afford. She did not have to do manual labor and could afford to wear impractical and delicate clothing.

Restraint

Because of the way that the clothing restrained her, it demonstrated to society her wealth. The type of clothing she chose to wear “served as an indication that [she] had servants and did not have to perform household tasks or work outside of the home.”5 Clothing from the late nineteenth century visibly defined the gap between the rich and the poor. These clothes were a “form of social control that contributed to the maintenance of women in dependent, subservient roles.”6 These garments were used to control her and since women did not have their own money, the complex garments they wore showed there father's or husband’s wealth.

Fabric Used

One aspect of clothing that demonstrated this class divide besides the restrictiveness of the clothing was the skirt sizes. A wide circumference of skirts went in and out of style throughout these decades. But these huge skirts required much more fabric than a more fitted skirt, which drove the price of the garment up, making it more difficult for lower-class women to afford. Wide skirts used significantly more fabric to fit and sculpt and since fabric was more expensive than labor in the late 1800s, having a wide skirt was a sign of wealth.

Getting Dressed

A woman with servants had more time to dress extravagantly since she did not have to do housework that other women were expected to do. She would also have servants to help her dress which meant that she could dress in a more complex way than a woman who did not have servants. A woman would not look as polished if she had to get dressed by herself, as clothing from the late nineteenth century was delicate and finicky.

The Families Wealth

Wealthy women dressed in this over-the-top way to announce to society that they were married to rich and powerful men and stood high in society themselves. Men’s fashion changed little over this time so it was up to women’s clothing to demonstrate the finances of the family. Men were expected to dress in a very specific, practical, business-like way that changed little over the decades compared to women’s fashion. There were also fewer differences between how upper-and middle-class men dressed so it became up to the women in the family to show their wealth through the way that they dressed.

The Dressmaker

It was rare for a middle-class woman to have a dress

maker make an entire dress, often the dressmaker would make portions of the dress and the woman would construct it herself, or in other cases, the woman would make the garment entirely by herself. Magazines would have directions on how to construct a garment or how to alter an out-of-date piece into something more stylish. The extravagance and detail of the dress showed that she was able to afford the time it would take her to complete the dress and it showed she did not have to do other domestic work that would otherwise consume her time. She was able to afford the time commitment it took to make a dress so extravagant and she was able to afford the fabric and the other materials.

maker make an entire dress, often the dressmaker would make portions of the dress and the woman would construct it herself, or in other cases, the woman would make the garment entirely by herself. Magazines would have directions on how to construct a garment or how to alter an out-of-date piece into something more stylish. The extravagance and detail of the dress showed that she was able to afford the time it would take her to complete the dress and it showed she did not have to do other domestic work that would otherwise consume her time. She was able to afford the time commitment it took to make a dress so extravagant and she was able to afford the fabric and the other materials.

1 Lurie, Alison. Language of Clothes. New York: Vintage 69.

2 Johnson, Lacey. “The Evolution of Fashion: Clothing of Upper Class American Women from 1865 to 1920.” Master's thesis, Ouachita Baptist University, 2014 16.

3 Johnson, 40.

4 Johnson, 60

5 Crane, Diana. "Clothing Behavior as Non-Verbal Resistance: Marginal Women and Alterna 60 - tive Dress in the Nineteenth Century." Fashion Theory 3, no. 2 (1999): 241-68. 242.

6 Crane, 254.

Class Divide

Everyday Difficulties

Continue Reading